Introduction

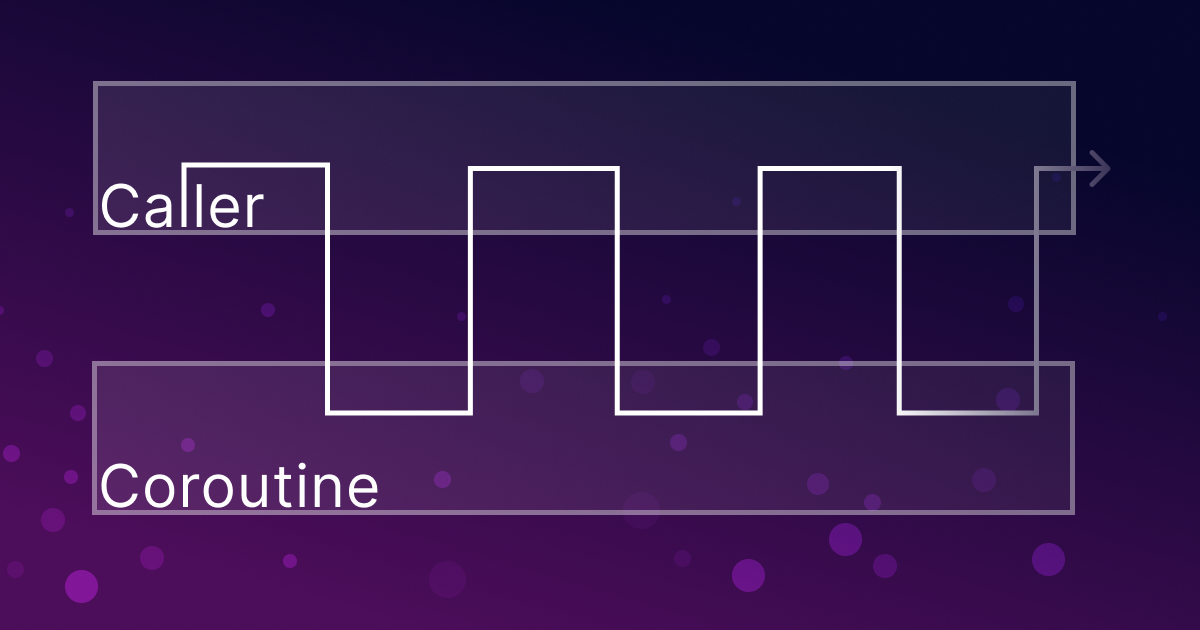

Icinga 2 makes heavy use of Boost.Coroutine2 in our network code, which are stackful coroutines that are designed to work well with the IO operations from Boost.Asio. This has proven to be a challenge whenever we wanted to asynchronously await things other than the result of said IO results. Since C++ has standardized its own implementation of coroutines in C++20, I wanted to take a look and see if the could be an alternative.

“Stackful” in the case of boost’s coroutines means the functions spawned as coroutines can call other functions and still be suspended at any point in their call-stack by using asynchronous operations.

In contrast, the coroutines added in the C++20 standard are stackless. Local variables inside the coroutine are located by the compiler inside a coroutine frame on the heap. Waiting for the completion of async operations is achieved through a new co_await operator that suspends the coroutine at a well-defined points from where it can later be resumed. This however means that these coroutines can’t directly call other functions that use async operations.

Since most of our asynchronous code is structured in nested functions it would be nice if we can also implement some form of nesting with the standard coroutines (i.e. something like coroutines awaiting coroutines).

Terminology

Before we get into the first example, let me clarify some of the terminology used by C++20 coroutines:

- Coroutine Function

- The function that actually implements the coroutine (

Print()in the example below). A coroutine is any function that has a valid handle as its return-type and uses one of the operatorsco_await,co_yieldorco_returnin its body. - Handle

- The type returned by the coroutine which defines the promise type of the coroutine. Handle objects provide a convenient way to

.resume()and.destroy()coroutines and can be copied or destroyed at any time without affecting the coroutine itself. They can also be reconstructed from the promise object at any time. The handles also implicitly convert to the type-erasedstd::coroutine_handle<>, that can still be used without any performance cost to resume the coroutine. The last part comes in pretty handy when processing coroutines in a queue as part of a thread-pool. - Promise

- Is stored as a part of the coroutine frame and will be allocated on the heap when the coroutine is started. It has to implement an interface that describes how the coroutine operates and can store additional variables for management of the coroutine.

- Awaitable

- A type that implements the interface needed by the co_await operator and can hold the return type.

Now to start off, let’s look at the simplest example possible:

Minimal Example

#include <coroutine>

#include <iostream>

struct Promise;

struct Handle : std::coroutine_handle<Promise> {

using promise_type = Promise;

};

struct Awaitable {

std::string retStr;

bool await_ready() { return false; }

void await_suspend(std::coroutine_handle<> h) {}

std::string await_resume() { return retStr; }

};

struct Promise {

Handle get_return_object() { return {Handle::from_promise(*this)}; }

std::suspend_always initial_suspend() noexcept { return {}; }

std::suspend_always final_suspend() noexcept { return {}; }

void return_void() {}

void unhandled_exception() {}

};

Handle Print(Awaitable &a) { std::cout << co_await a; }

int main(void) {

Awaitable a;

auto printCoro = Print(a);

printCoro.resume();

a.retStr = "Hello World";

printCoro.resume();

printCoro.destroy();

return 0;

}

Beginning from the main function, the following things happen:

- An awaitable object is initialized.

- A coroutine is started, stores a reference to the awaitable in the coroutine frame and due to initial_suspend() returning

std::suspend_alwaysit suspends immediately before any of the function body is executed. - We then call the

.resume()method with begins executing the coroutine function body. - Through the

co_awaitoperator it then calls theawait_suspend()function of the awaitable (currently a noop), and returns control tomain(). - We then store the string “Hello World” in our awaitable object, and resume the coroutine.

- Resuming the coroutine calls

await_resume()and returns the string stored in the awaitable. - The coroutine then receives this string returned from

await_resume()and prints it to stdout. - Finally, since the coroutine has completed, we destroy it manually.

It is already becoming clear that there’s a lot of flexibility to this interface. Using another part of the interface, the await_transform() function, we can transform a coroutine handle into an awaitable, allowing us to co_await other coroutines:

Awaiting a Coroutine

#include <coroutine>

#include <iostream>

struct Promise;

struct Handle : std::coroutine_handle<Promise> {

using promise_type = Promise;

};

struct Awaitable {

std::string &retStr;

bool await_ready() { return false; }

void await_suspend(std::coroutine_handle<> h) {}

std::string await_resume() { return retStr; }

};

struct Promise {

Handle get_return_object() { return {Handle::from_promise(*this)}; }

std::suspend_always initial_suspend() noexcept { return {}; }

std::suspend_always final_suspend() noexcept { return {}; }

void return_value(std::string str) { retStr = str; }

void unhandled_exception() {}

Awaitable await_transform(Handle h) { return {h.promise().retStr}; }

std::string retStr;

};

Handle Print(Handle a) {

std::cout << co_await a;

co_return ""; // Ignore this

}

Handle Read() { co_return "Hello World"; }

int main(void) {

auto readCoro = Read();

auto printCoro = Print(readCoro);

printCoro.resume();

readCoro.resume();

printCoro.resume();

readCoro.destroy();

printCoro.destroy();

return 0;

}

Here’s what changed:

- Now instead of passing an awaitable to our coroutine, we pass the handle of a second coroutine.

- The

Print()coroutine then reaches theco_awaitoperator and calls the optionalawait_transform()method with the handle of the awaited coroutine. - This prepares an awaitable that holds a reference to the return string in the promise associated with the

Read()coroutine. Then thePrint()coroutine is suspended. - We then resume the

Read()coroutine and it uses co_return to set the return value stored in its promise. - As we resume the

Print()coroutine again,await_resume()gets called and the return value is printed same as in the previous example. - You might have noticed that

Print()now also returns a value viaco_return, which is only necessary because a promise type can only have one return type. For sake of simplicity I tried to stick with a single non-templated promise type. In practice you’d want the Handle and promise types templated by the coroutine’s return type, soPrint()would returnHandle<void>andRead()would returnHandle<std::string>.

So far so good, but obviously we wouldn’t want to resume the coroutines manually all the time. Consider the next example:

Seamlessly nested coroutines

#include <coroutine>

#include <iostream>

struct Promise;

struct Handle : std::coroutine_handle<Promise> {

using promise_type = Promise;

};

struct Awaitable {

std::string &retStr;

std::coroutine_handle<> awaited;

bool await_ready() { return false; }

std::coroutine_handle<> await_suspend(std::coroutine_handle<> h) {

return awaited;

}

std::string await_resume() {

auto retVal = std::move(retStr);

awaited.destroy();

return retVal;

}

};

struct ResumeAwaitable {

std::coroutine_handle<> resumeHandle;

bool await_ready() noexcept { return false; }

std::coroutine_handle<> await_suspend(std::coroutine_handle<> h) noexcept {

if (resumeHandle) {

return resumeHandle;

}

h.destroy();

return std::noop_coroutine();

}

void await_resume() noexcept {}

};

struct Promise {

std::string retStr;

std::coroutine_handle<> resumeHandle;

Handle get_return_object() { return {Handle::from_promise(*this)}; }

std::suspend_always initial_suspend() noexcept { return {}; }

ResumeAwaitable final_suspend() noexcept { return {resumeHandle}; }

void return_value(std::string str) { retStr = str; }

void unhandled_exception() {}

Awaitable await_transform(Handle h) {

h.promise().resumeHandle = Handle::from_promise(*this);

return {h.promise().retStr, h};

}

};

Handle Read() { co_return "Hello World"; }

Handle Print() {

std::cout << co_await Read();

co_return ""; // Ignore this

}

int main(void) {

auto coro = Print();

coro.resume();

return 0;

}

Now, instead of co_await returning back to the execution context after suspension, await_suspend() returns the stored handle of the Read() coroutine. When returning a handle in this way, execution will continue in that coroutine instead of returning to its caller/resumer.

So far we haven’t looked at what std::suspend_always actually is. Together with std::suspend_never these are predefined awaitable types that either always suspend immediately or not at all. The final_suspend() method usually returns one of these to control if the coroutine gets destroyed or not once it completes. For example if you return std::suspend_always here, the coroutine is always suspended right before destruction, leaving that up to whoever manages the coroutine handle.

But as we know know, the await_suspend() function of an awaitable can also return a coroutine handle itself for seamless continuation. We can use this by returning the new ResumeAwaitable instead, which when constructed with a handle, always continues by resuming that handle. So now, when Read() completes, it automatically resumes the Print() coroutine where it has left off. Almost like a call-stack.

Destruction is now also handled automatically, by either destroying the coroutine once the awaitable has retrieved the return value, or in case there is no resumable coroutine, during the final_suspend().

Making this useful

Of course, since this is just an example, Read() doesn’t actually read anything, but always immediately co_returns a value. In practice you can co_await all kinds of things as long as the awaitable concept is satisfied and the coroutine is resumed when the work is done. For example, in recent versions Boost.Asio’s IO-operations support co_await by passing boost::asio::use_awaitable as a completion token:

std::size_t bytes = co_await socket.async_read_some(asio::buffer(buffer), asio::use_awaitable);

And to really be useful you’d want to extend this by making the types more generic and flexible. As mentioned before you can make the Handle and Promise types templated to allow for any type of return values, and you can also use the unhandled_exception() method to forward and rethrow exceptions thrown inside a coroutine, similar to how the return value is propagated. Finally, you’d want some kind of executor type to wrap the execution of the “outermost” coroutine handles, something like a thread pool that works through a queue of the type-erased std::coroutine_handle<> handles.

Advantages

- Standard coroutines don’t require platform specific hacks or assembly to work.

- Stackful coroutines require to specify their stack size up-front, forcing you to estimate how much is needed for a given coroutine. In our case we currently generously provision for a maximum stack size of 265kB per coroutine. Which in the case of our REST API needs to be doubled because we have two coroutines running in parallel, resulting in an impact of 512kB per HTTP connection. With the stackless coroutines, each frame on its own takes up about 16-80 byte depending on optimization, plus the actual space needed for the promise objects and local variables. Essentially, with stackless coroutines you pay for what you use, when you use it, instead of for what you might conceivably use in case of stackful coroutines.

- There’s also the possibility for the compiler to inline the entire coroutine when it can prove the lifetime of the frame, in which case it doesn’t require any allocations at all. However, while this might be possible in the above example, or some self-contained generator code, it likely won’t be possible in most production code.

- The standard coroutines give a lot more flexibility to write custom awaitables outside of general IO, and aren’t restricted to a single library’s way of doing async. While it is possible to implement custom operations with Boost.Asio that also support stackful coroutines (like the promise/future type I’ve attempted at in PR #10626), the interface is rather crude and verbose, changes a lot between versions and to me doesn’t really seem intended for application developers to use.

Conclusion

There are definitely some advantages to the standard coroutines, but I don’t foresee Icinga 2 quickly replacing Boost.Coroutine2. For one our code base isn’t on C++20 yet and that may still take a while. Also the advantages probably don’t justify to switch everything over at once. But once we’re on C++20 I see no reason not to start laying the foundations and gradually moving over some of our code-base wherever we can benefit the greater flexibility.